This post is a part of the “Career Fundamentals” series.

How to become comfortable & confident with self-guided projects and learning.

Why Learn Hands On?

These days, it feels like there’s almost too many learning methods available to us: videos, books, courses, podcasts… the list goes on! But no matter what method of learning I use, I always come back to one method alongside all the others when it comes to going in-depth on a topic: Self-guided, hands on practice.

This can look like time wasted when more curated content is so accessible. Why spend time troubleshooting when the answers are available? Why bang our head against the keyboard when we could’ve followed a step-by-step guide? But if we never step off the guided path, we’ll never truly learn what’s needed of us to solve technical problems for ourselves, or on the job. That’s what we’re actually training for, right?

This thinking develops best when we’re challenged to find answers on our own, like practicing a new instrument or building muscle. This is exactly the kind of “problem solving muscle” that we need to solve new challenges on the job.

How To Do This?

If you’re not accustomed to it, technical hands on learning can feel intimidating. What are you even supposed to do to go “hands on”? Does it mean massive home labs, or giant blocks of code on GitHub? When I started out, I was worried this meant taking on massive coding projects I’d never understand.

It took me some time to realize this doesn’t have to be overwhelming, and it doesn’t need massive output to have a major impact. By taking steps into small projects first, you’ll be able to spend your time building knowledge without getting frustrated from too much too fast.

In the post below are three methods I find helpful to ease into hands on learning: Documents, Scripts, and Projects. These three techniques will build on each other, and have helped me greatly over the years to deepen my understanding of security.

While there will always be plenty of CTFs, labs, and puzzles you can explore.. there’s something especially powerful about taking on an unscripted objective of your own.

Technique 1: Documents

The least intimidating method I’ve found to start working with a new topic is documentation. This could be my tendency towards taking notes, but I also believe there’s comfort in setting a limited scope around creating a cheatsheet or wiki page for your personal reference.

Choose a topic or sub-topic you’re learning about and build out a personal reference page on it for later. You can then add this reference to a personal wiki, and then use it whenever you need to (CTFs, exam prep, interview prep, etc). You could also create an introductory talk for this method, creating a set of slides you can share and reference. Over time, these notes accumulate to years of knowledge, making it simple to come back to what you’ve learned. They can also be shared with peers, developing your understanding by teaching a topic.

Example

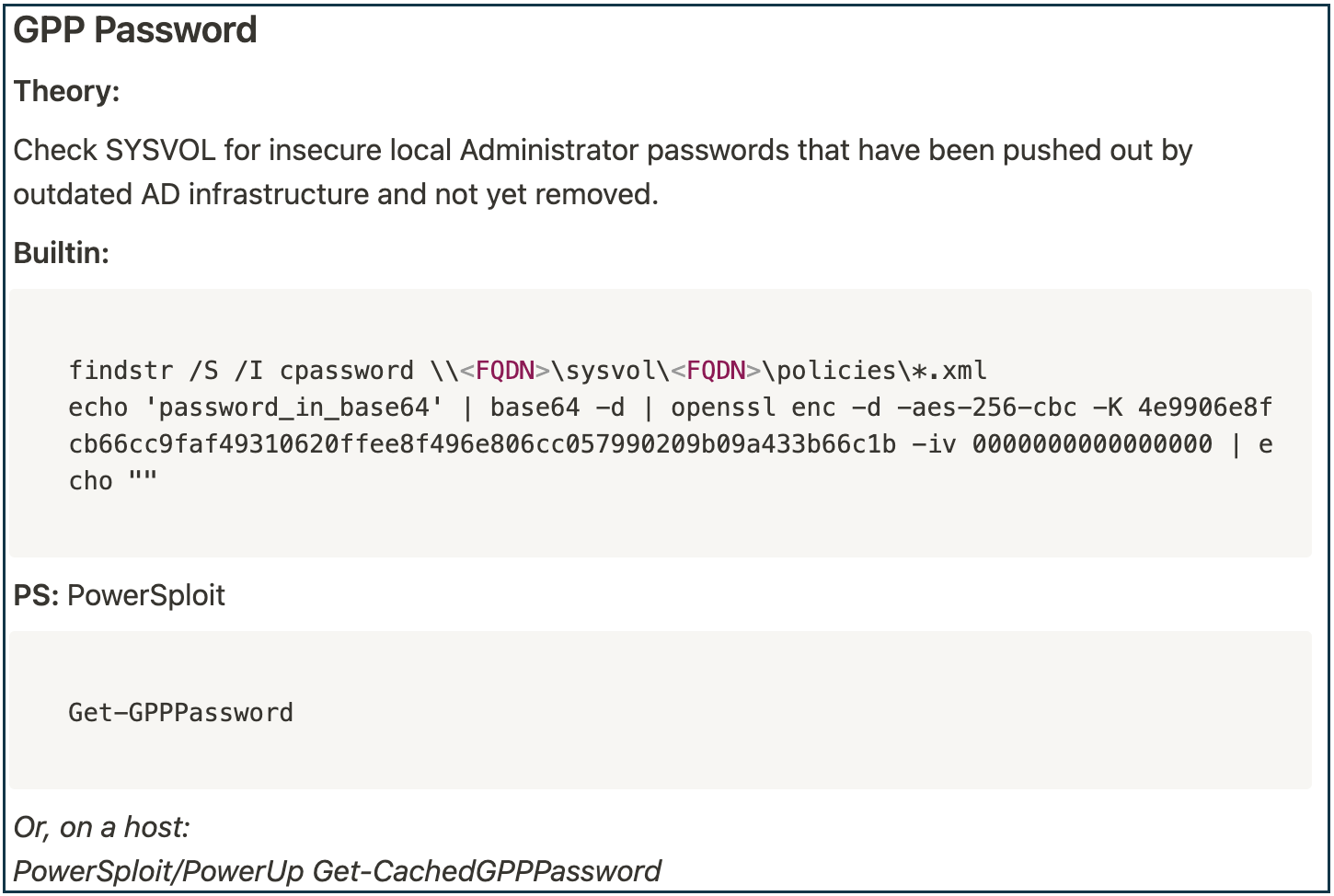

As an example of this, during previous work pentesting Active Directory (AD) I dedicated some study time to understanding the “GPP Password” vulnerability. This vulnerability was published in 2015 by Sean Metcalf, in his blog “Finding Passwords in SYSVOL & Exploiting Group Policy Preferences”. I wanted to understand this topic clearly, as it wasn’t uncommon to see files related to this vulnerability on large client networks I was reviewing at the time. I needed to be able to test for it fast, and explain it quickly to my clients’ CISOs. I also didn’t have the time to read the full post whenever I was on a client engagement.

Based on this post and some additional research, I created the following personal reference:

Very simple, right?

Benefits

Writing this quick section pushed me to get hands on by:

- Executing the “findstr” command Sean provided against test GPP files to identify these passwords, so I was familiar with the process.

- Verifying a one-liner to decode and decrypt the password in native Linux tools (what I usually had available), to replace Sean’s PowerShell decoding.

- Testing a “cheat code” for doing this all in one now that I understood it, with PowerShell modules others built (in PowerSploit) based on this research.

While I could have referenced an “offensive wiki” for this knowledge (like the great resources at ired.team), by building this snippet myself and continuing the process for other common AD hacking topics I was prepared to run these attacks professionally and safely on a client engagement. I had made the knowledge my own, and was ready to explain it.

Technique 2: Scripts

Small scripts and tools make a fantastic step up from documentation. They can teach a lot about a language and topic in just a few lines. Since the scope is small, they’re also much less intimidating than sitting down to complete a full, complex project - especially if you don’t consider yourself a natural coder.

Choose a topic you’ve been learning about, and a simple language that lines up with the system you currently use (PowerShell, Bash, and Python are great candidates). Aim to complete a small task with code in this language, even if it’s been done before. Some great examples I’ve seen include making a mini port scanner, resolving hostnames to IPs, or querying a web API. The more comfortable you get, the more complex you can make your tasks.

Example

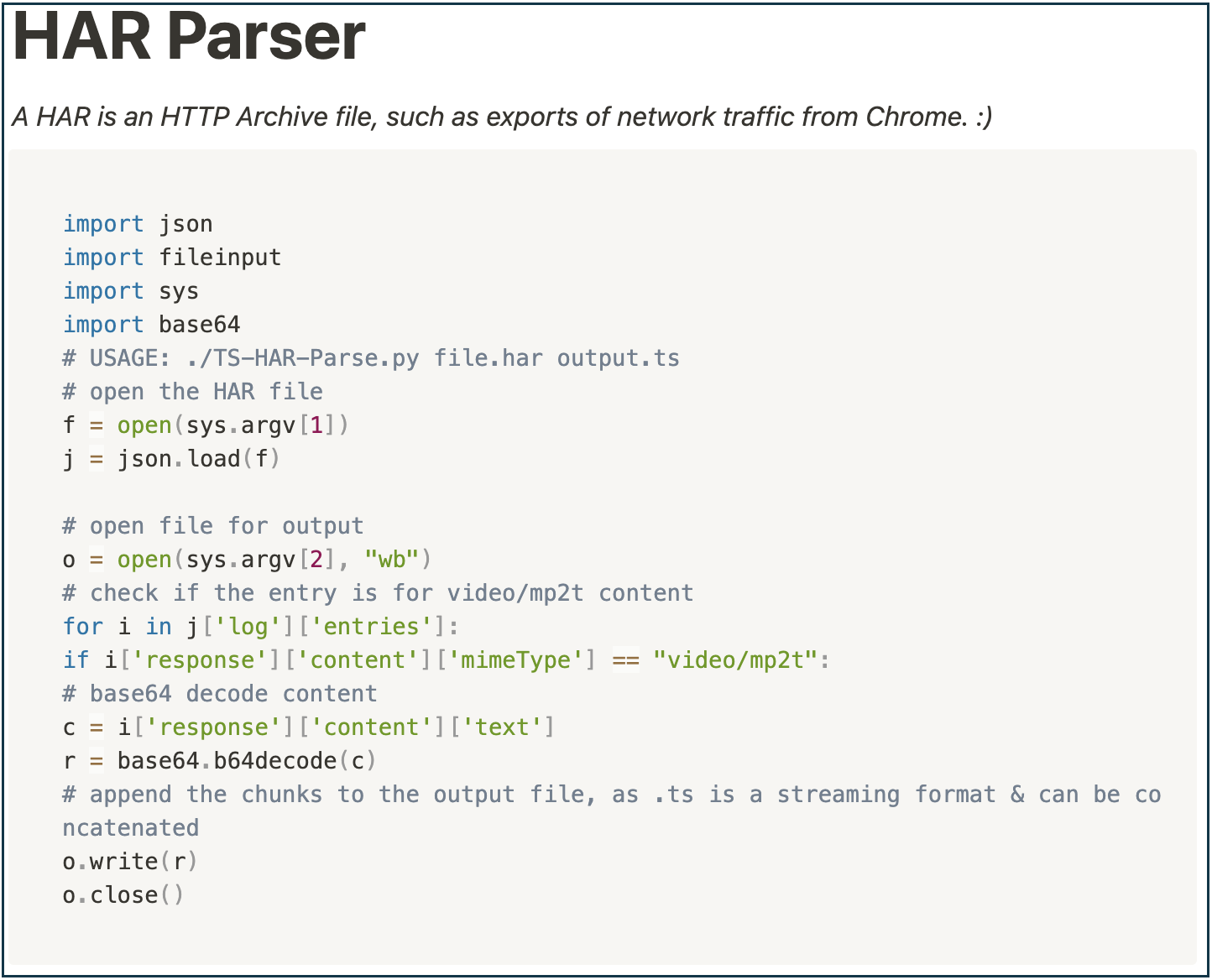

In the past, I spent some time learning about the HTTP Archive Files (HAR) that Google Chrome uses to store network traffic within its Developer Tools. While I could have looked into a Chrome extension or existing Python script for this, I wanted to take the time to understand the file format and the chance to work with JSON in code.

Streaming traffic (video & audio) seemed like a fun target to assess, so I created the below code to carve out the “.ts” files associated with streaming from a network capture:

(Also available on GitHub: TS-HAR-Parser.py)

(Also available on GitHub: TS-HAR-Parser.py)

Benefits

This code built my familiarity with the following concepts:

- Working with input & output files in Python (using the fileinput library), a concept I was still getting familiar with.

- Processing JSON format data and conditionals, something I was very uncomfortable with.

- Understanding how Chrome captures and processes network traffic in the Developer Tools using HAR files through interacting with these files, and watching network traffic come in through the tools console.

This is now something I can come back to as a Python reference for working with JSON, files, and base64 decoding. Now that I have code I’ve written with these concepts, I don’t need to look through poorly formatted answers on Stack Overflow to remember these concepts - I already have the real world syntax on hand! And of course, this is always fun to come back to for more stream parsing.

Technique 3: Projects

Once you’ve written some documents and scripts, you’ll start to a project isn’t as crazy as it seemed. In this case, I’m going to define a “Project” as “combining code or docs into a larger effort”. If you’ve been working up to more complex documents or scripts with the first two techniques, a large project will start looking like a collection of smaller tasks.

Projects take many forms, and will depend on what you’d like to focus on for a slightly longer time. To start, think about a topic you really want to deepen your knowledge on: If you’re new to cybersecurity, this may be a core topic like networking, operating systems, or general coding. Once you have more experience, it may be a specific niche like web application pentesting, forensics, or cloud platforms.

Your topic will determine your format. Some great candidates include:

- Developing a multi-module tool in Python for any reason, serious or fun.

- Home lab networks combining routing and operating system skills (Jeff McJunkin has a great post on home labs in “Build Your Own Kickass Home Lab”).

- Multi page documentation “wikis” that combine tool usage notes with documentation for live response or pentesting.

This doesn’t have to be something new. If you previously wrote a mini port scanner and want to expand it to include vulnerability scanning, great! As you build new features, you’ll likely want to build a small home network to test against as well. Projects can start small, and branch into new areas the more you work on them. One of my small projects involves playing with Hue lightbulbs in Python. I haven’t gotten very far, but I’ve learned a lot!

Tips for Project Success

To be successful with a larger project, some points to keep in mind are:

- Choose something interesting: Pick a topic you’re insatiably curious about, or look for a way to make a topic you need to learn more fun.

- Take small steps: Break down larger goals into sub-goals and tasks that become smaller, less intimidating projects to complete.

- Take breaks: If you need a pause from a project, it’s okay to put it on hold. A personal project left paused will still provide great training for the time you’ve invested.

- Have fun: Projects like this will usually land on your personal time, so have fun! Don’t pressure yourself, and take time to enjoy the work. Give your lab systems creative names. Put on some hacking tunes. Let yourself get lost in the work.

- Don’t worry: This doesn’t have to be for your public portfolio (Github). Code written on your own laptop locally for a day is as good as any to teach you new ideas and start applying them.

Conclusion

Hands on learning can be intimidating. But it also offers a challenge that will level up your career, from first interviews up through senior security roles. I truly believe this mindset shift has made my career infinitely more rewarding than sticking to the books alone on learning new material. If you’re newer to the field, it’s my hope that this post helps you give it a shot! Which method will you start with?

Image Credit: Unsplash